When musical prodigy Idil Biret, a lighthearted seven-year old irresistible force with bouncy corkscrew curls, met the immovable object of Nadia Boulanger’s iron will, fierce discipline, and aesthetic certainty, a lifetime of artistic creativity exploded onto the musical world.

In her native Turkey, Idil Biret was a cultural avatar from the moment in 1946 when President İsmet İnönü requested an unplanned performance following a chamber music concert attended by diplomats and political leaders in Ankara. She played the Prelude in C Major from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier in one go, then moved on to the C Minor Prelude. The five-year-old’s performance had a tremendous impact on Turkey’s political elite. At the next session of the Turkish Parliament, a special act was passed—Idil’s Law—providing for her training at the Paris Conservatoire.

Idil Biret and Nadia Boulanger met in Paris. At age seven, Idil enjoyed playing the piano tremendously—with an emphasis on the word “play”. Her overwhelming aptitude for music emerged early, at three, as she listened to music on the radio, absorbed the notes, and played the melodies on the keyboard. What fun! Soon she was playing harmonies and chords, sometimes using her elbows when the span was wider than her tiny hands. Without formal training, who knows? She might have become the world’s greatest ragtime pianist, but her free spirit was now bound by act of parliament to different destiny: to become an outstanding classical pianist of her generation, performing with major orchestras around the world, with a recording legacy of extraordinary breadth.

As a child Idil Biret formed a deep bond with music, and her natural genius has won her global acclaim as a performer and as a teacher. Many are familiar with Idil Biret the pianist. After all, she has two million monthly listeners on Spotify, topping Martha Argerich by a half million, and more than the total listeners of Vladimir Horowitz, Arthur Rubenstein and Sviatoslav Richter combined!

But there is another, equally important role Idil Biret has played in her life. She was born in 1941 into the bright day of outward-facing secularism and open-mindedness in a nation looking abroad for the best practices and ideas to adopt into Turkish culture. She was sent to Paris by a Turkish legislature enthusiastic about embracing European culture so she could learn from the most renowned teachers in the musical world. It was this same cultural expansiveness that brought many Turks of her generation to the United States and Europe not just as students but as lifelong global citizens loving the best of all cultures. Throughout a career spanning eight decades, Idil Biret has been celebrated as an avatar of what is best in Turkish culture. Turkish newspapers ran weekly illustrated tales of her life in Paris for their young readers. Streets have been named after her throughout Turkey, and thousands of girls are named “Idil” each year.

The amazing trajectory of Biret’s life embodies the ideals of the Turkish cultural renaissance initiated by Kemal Atatürk, founder of the modern Turkish republic, as a means to bring the young republic out of the grips of sclerotic, self-absorbed Ottoman conservatism into the full daylight of European civilization. Wilhelm Kempff, a lifelong mentor to Idil Biret, was a key figure in Turkey’s cultural expansion and modernization. In a Bayerischer Rundfunk public service radio program recorded in 1995, Biret describes the first meeting of the great German pianist with the great Turkish revolutionary and statesman as Kempff related it to her in June 1982, when she was visiting with Kempff at his villa overlooking the Mediterranean in the village of Positano on the Amalfi coast.

Later, after dinner, the question of his first visit to Turkey was posed. Was it in the 1930s? “No, much earlier” was Kempff ’s reply. “I first visited Turkey in 1927. I gave a recital in Ankara at the Halkevi.44 Kemal Pasha then invited me for dinner with his friends at the Presidential residence. There was a large gathering of people in the evening and the dinner lasted until about 11:00 p.m.

As the guests were leaving, he asked me to stay behind, and when everyone was gone, we passed into his study. There, Kemal Pasha started the conversation by saying that as part of a drive for modernization in Turkey he was introducing many reforms in law, education, and other areas affecting the public life.

He continued to say that classical music was an inte- gral part of the Western culture, the source of his reform movement. He therefore felt the necessity of the wide- spread introduction of classical music in Turkey as part of the drive towards modernization in the country.

Kemal Pasha said he was afraid that without also parallel reforms in music in Turkey, his reforms in other areas would remain incomplete. Kemal Pasha then asked my thoughts on how this could be achieved, the schools, institutions to be formed for this purpose and the eminent musicians and musicologists I may recommend for invitation to Turkey to help build the foundations of classical music.

There can be no revolution without music, Atatürk believed. Classical music was integral to European culture, and European culture was the source of his reform movement. Kempff brought Paul Hindemith to Atatürk’s attention. The rising star of composition was promptly engaged by Atatürk to help found the state conservatory in Ankara and to organize Turkey’s system of musical education.

The Turkish cultural revolution went far beyond music. Never hesitant to take sweeping measures, Atatürk took advantage of the fact that the Turkish population was largely illiterate and in 1928 personally introduced his newly alphabetized Turkish language to the country. Thereafter, the Arabic script of written Turkish—never a good fit—was eliminated, and fifteen million illiterate Turks learned to read and pronounce their native language using the Western alphabet.

Educated and cultured Turks rejoiced at the opening of the country toward the best of what Europe had to offer, and even common people could take pride in sending this enormously talented curly headed girl to represent Turkey on the European stage. The legislature was unanimous in its vote to provide funds. For many, Biret was an expression of the “natural joy” of the Turkish people. “The nation has shed its blood to correct its errors: It is now at peace and can give vent to its natural joy,” Atatürk exclaimed in 1928, maintaining that traditional Ottoman music, “this simple music, can no longer satisfy the highly developed soul and feelings of the Turk.”

Nadia Boulanger was to show her support of classical music in Turkey; after all, she had been entrusted with the education of Turkey’s most outstanding musical prodigy. After Biret graduated from the Paris Conservatory, Boulanger, with the help of Mithat Fenmen, arranged for Biret to play in two concerts in September 1958 in Istanbul and Ankara. The program consisted of three concertos: Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 24 in C Minor, K. 491; the Symphonic Variations of César Franck; and Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 54. At sixteen, Biret found the tour schedule demanding and, frankly, would have preferred to use the beautiful September weather to swim in the refreshing waters of Moda Bay below her family apartment instead of practicing for her performances. Years later, Biret recalled,

The rehearsals with the orchestra had begun and also the socializing (dinners, cocktail parties, et cetera). I was not looking forward to these gatherings, as I was of an age where I didn’t quite belong to the adult world but was not anymore a child. During one of these parties, I started to drink what I thought was a lemonade. After two or more of these delicious nectars, we were invited to join the dinner table. I felt wonderful, a little weightless maybe.

. . . .Nothing mattered anymore. . . . The piercing looks of Nadia Boulanger and my mother were immediately on me. I was then trying to explain to my neighbor, a nice elderly gentleman, that I was feeling slightly bizarre, as I had some of the tasty lemonade before. The gentleman exclaimed, “You had not lemonade but a white ladies’ cock- tail, you poor thing!” Neither my mother, nor Mademoiselle Boulanger, was amused by this incident.

Throughout the tour, the strict control I experienced

continued to function in daily life and in music. My teacher was even conducting the cadenzas, where I was supposed to be free. . . . So I didn’t keep fond memories of this Turkish tour in general. Nadia Boulanger was visiting museums, attending parties and dinners, meeting officials with her usual boundless energy. In Ankara, she found a great new friend in the person of Mr. C. M. Altar, an extremely cultured, refined musicologist who was under- secretary at the Ministry of Culture. Whenever a problem arose, Mlle Boulanger would say, “I trust my dear Mr. Altar will find the right solution.” And she was right. One of the great moments occurred when Mlle Boulanger met my grandmother: two formidable women facing each other! They were only able to communicate verbally through the help of a translator, but they could understand and feel far better in a sort of telepathic way when they were in the presence of each other.

Another tour of Turkey took place in 1962, Boulanger conducting the orchestra and Biret the piano soloist. “The Turkish government treated Boulanger like visiting royalty, assigning her a lady-in-waiting and rooms in the most elegant hotels,” notes Biret. The relationship between Boulanger and Biret was deep yet fraught. “God sent me this child who is the soul of my sister Lili. It’s unbelievable!” Boulanger confided to a friend. She once gave Biret a card picturing an angel with these words: “To my little Idil, Christmas 1959. May the Angel guide and protect her on the beautiful and perilous path she has started upon.”

Yet Biret felt uncomfortable with Boulanger’s strictness and inflexibility: “In spite of my great affection and respect for Mlle. Boulanger, I felt somewhat cramped under her direction. She disciplined me and would not allow me any freedom, even in the cadenzas.”

Biret continued to bring brilliant pianism to audiences around the world, give master classes, and broaden her recorded repertoire into her eighties. In April 2020, Istanbul’s Bosphorus Bridge connecting Europe with Asia was closed by the Turkish government for COVID lockdown. A concert grand piano was placed at its exact center. There, at the precise spot Europe and Asia meet, Biret played Liszt’s piano transcription of “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the anthem of the European Union and of the Council of Europe. Representing the whole of Europe, its purpose is to honor shared European values of freedom, peace, and solidarity.

This highly symbolic performance was recorded by the Directorate of Communications of the Presidency of the Republic of Turkey and released on its YouTube channel as “A call for love and unity . . . to the whole world.” Who could better represent the unity of Asia with Europe, of Turkey with the world, than Idil Biret? Despite this propaganda piece (or conceptual art, if you prefer), the cultural revolution started by Atatürk—Turkey’s embrace of European civilization, which Biret carried forward so magnificently for seven decades—is in its demise.

The start of Turkey’s turn to European civilization was symbolized by Atatürk’s conversion of the Hagia Sophia from mosque to museum in 1935, six years before Biret’s birth. The magnificent domed architectural masterpiece, built by the Roman emperor Justinian I over five years, from 532 to 537, for more than nine hundred years was the largest cathedral in Christendom—until, in 1453, Constantinople fell to attacking Ottoman forces. When Sultan Mehmed entered the city, he performed the Friday prayer and khutbah (sermon) in Hagia Sophia. This marked the official conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque and cemented the role of Ottoman sultans as preeminent leaders of both Islam and the empire.

In 1935 Atatürk’s rejected Islam as a state religion in order to form a secular state. 85 years later, on July 10, 2020, less than three months after Biret’s symbolic performance precisely on the border of Asia and Europe, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan reversed Atatürk’s conversion to secularism. Under Erdoğan’s thumb, the Turkish Council of State decreed that Hagia Sophia can be used only as a mosque and not for any other purpose. This blatant imitation of Sultan Mehmed’s conversion of church to mosque in 1453 made Erdoğan’s rejection of secularism absolutely clear. He attempts to cloak himself in a mantle of Ottoman supremacy, harking back to long-lost days of glory, when much of the Muslim world was under the central command of the reigning Ottoman sultan.

Time will tell whether Turkey’s Islamist leadership can successfully eradicate from Turkish culture this eighty-five-year opening to European cultural values.

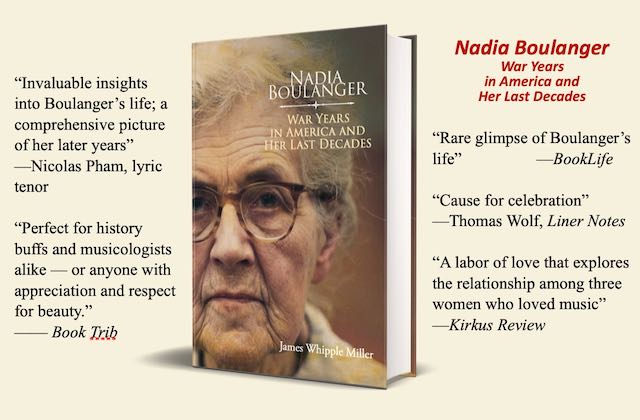

For a detailed account of the lives and personalities of Nadia Boulanger, Idil Biret, and American musician Ruth Robbins, see the incisive biographical study by Idil Biret Education Initiative founder James Whipple Miller, Nadia Boulanger: War Years in America and Her Last Decades.

© 2023 James Whipple Miller